Home > Information > News

#News ·2025-01-09

A warm knowledge:

The United Nations has declared this year "the Year of quantum Science and Technology."

Because exactly 100 years ago, in 1925, it was the German physicist Heisenberg who published a paper called "Quantum Mechanical Reinterpretation of Kinematics and Mechanical Relations" as a starting point, the modern era of quantum mechanics, the gears began to turn.

△ Photo source: Wikipedia

Here's another trivia:

In a matter of months in 1925, quantum mechanics set off an astonishing revolution in the basic understanding of physics that continues to this day.

So we're kind of curious, how did quantum mechanics emerge in a matter of months a century ago?

Today, the journal Nature released an article called "How quantum mechanics emerged in a few revolutionary months 100 years ago," which takes us back

What was physics like before quantum mechanics?

More than 100 years ago, in the early 20th century, classical physics could not explain subatomic phenomena, so the concept of quantum began to be introduced.

But the heart of the old quantum theory was the Bohr Sommerfeld model developed in 1910s.

This model, proposed by the Danish physicist Niels Bohr and the German physicist Arnold Sommerfeld, opened up new avenues for the study of atomic structure.

Bohr (left) and Sommerfeld (right)

By assuming that electrons move in elliptical orbits around the nucleus and are subject to certain quantization conditions, the Bohr Sommerfeld model provides a set of rules for selecting certain "permissible" orbits for classical systems (in the case of hydrogen atoms, electrons moving around protons), resulting in calculated values that agree with the observed energy spectrum.

The model successfully explains the spectrum of the hydrogen atom - which consists of only one proton and one electron - and the splitting of spectral lines in the presence of an applied electric field (the Stark effect) or magnetic field (the ordinary Zeeman effect).

However, this model still has shortcomings, as Werner Heisenberg discovered.

△ Werner Heisenberg

In 1923, Heisenberg joined the Institute for Theoretical Physics at the University of Gottingen in Germany, where he became an assistant to theoretical physicist Max Born.

Soon after, Heisenberg discovered that the Bohr Sommerfeld model encountered a series of problems when dealing with hydrogen molecules and atoms with multiple electrons

Heisenberg and Born made a series of detailed calculations of the spectra of helium atoms using all the orbitals allowed by the Bohr Sommerfeld model, but their results did not agree with experimental observations.

At first, the two suspected a miscalculation, but soon the doubts focused on a more fundamental point. As Born wrote in his notes:

There is a growing possibility that the scientific community will need to come up with new hypotheses, not just in the sense of physical hypotheses.

More likely, the entire conceptual system in physics may need to be rebuilt from scratch.

In December of the same year, Heisenberg wrote to Sommerfeld, his doctoral adviser, that "no model has any real meaning." The orbit is not real in terms of frequency or energy."

(p.s. Sommerfeld and Heisenberg went on to win Nobel Prizes)

Heisenberg continued to discuss these concerns with his peers.

For example, he corresponded so often with Wolfgang Pauli (whose PhD was also Sommerfeld and who later won a Nobel Prize) that Pauli became increasingly convinced that the idea of electrons moving in orbits was unreliable.

Sommerfeld heard them say in December 1924: "We are using a language that is inadequate to describe the simplicity and beauty of the quantum world."

But without an orbital model, what would you do?

No one knew, and Heisenberg fretted about it. As late as April 1925, Heisenberg wrote:

Quantum theory, in its current state, must rely on more or less symbolic, modeled images of electromechanical behavior based on classical theory.

After a few months of hard thinking, Heisenberg proposed a new core of quantum theory that seemed radical at the time

He decided to develop an innovative theory called "quantum mechanics."

In this theory, electrons are no longer seen as particles moving along a continuous trajectory, rather than building models of atoms based on the idea that electrons move along well-defined orbits in a classical way.

On July 9 of that year, Heisenberg wrote to Pauli:

"All my seemingly bad efforts are aimed at the total annihilation of the concept of 'orbit' - because in any case it is impossible to observe [coincidence]."

This was Heisenberg's decisive break with classical mechanics.

Heisenberg soon wrote the paper "Quantum Mechanical Reinterpretation of Kinematics and Mechanical Relations".

In the paper, he proposed "the establishment of a theoretical quantum mechanical foundation based only on the relationships between quantities that can be observed in principle."

Based on the classical equations of motion for periodic systems, Heisenberg proposed an equation for the motion of electrons that includes complex arrays of equal quantities such as position and momentum, such as the observable energy and the magnitude of the transition (the probability of an atom moving from one quantum state to another).

What brought Heisenberg to this point was despair at the heart of the old quantum theory.

Pragmatic considerations are at the heart of Heisenberg's physics. As Heisenberg explained in the introduction to his paper, given the complexity of dealing with atoms of multiple electrons, "it seems reasonable to give up observing hitherto unobservable quantities, such as the positions and periods of electrons".

However, it is difficult to see how methods for eliminating unobservable measurements should guide the further development of the theory.

Before a theory can describe phenomena such as collisions and the motion of free particles, it must include quantities other than energy and transition amplitudes; Beyond that, it wasn't even clear to quantum mechanics at the time which quantities should be considered unobservable.

The electron position, for example, was only re-accepted as "observable" in 1927.

Born reviewed and reflected more than a decade later, saying that in 1925, the idea of eliminating unobserved measurements was reasonable enough, but practice at the time often returned with this message:

Such a general and vague statement is rather useless, even misleading.

After the paper was published, Heisenberg was adamant that only deeper mathematical research would reveal whether the methods used in the paper "could be considered satisfactory."

In the months that followed, Born and the German physicist Paskool Jordan completed the task.

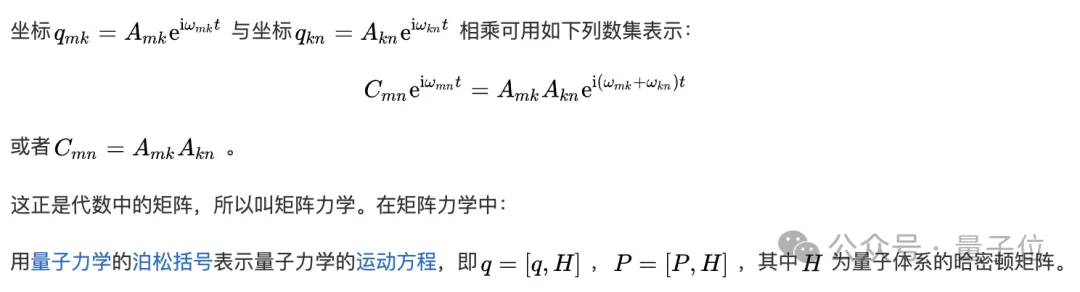

They realized that the quantities that appeared in Heisenberg's equations could be represented as matrices - a mathematical form that even at the time was unfamiliar to most physicists - and they reformulated the theory in these terms.

Thus, the curtain was slowly drawn on matrix mechanics, one of the expressions of quantum mechanics.

Born, Heisenberg, and Jordan presented a long paper on the innovative "matrix mechanics" in November 1925.

△ A brief look at matrix mechanics

But the new model also has new bugs.

One drawback of the new theory, the authors say, is that because the motion of electrons cannot be described in terms of familiar concepts such as space and time, the new model is not directly applicable to the interpretation of geometric visualizations.

Heisenberg wrote to Pauli in June 1925: What does the equation of motion mean?

Later, in December of the same year, Pauli successfully calculated the spectrum of the hydrogen atom using matrix mechanics, but most physicists still had a hard time accepting this obscure mathematics.

But things took a turn a few months later, as a more accepted approach emerged in the first half of 1926 with a series of seminal papers.

The papers were published by Erwin Schrodinger in the Annals of Physics.

(Yes, the Schrodinger you know, the Schrodinger who lives with cats.)

△ Erwin Schrodinger

In Schrodinger's view, the inability to describe the motion of an electron in space-time was an abdication of the physicist's responsibility and amounted to an abdication of any hope of understanding the inner workings of atoms.

So Schrodinger insists that such an understanding is possible.

In a footnote to one of the papers, Schrodinger confessed that he was "disgusted with the quantum mechanical approach of the Gottingen school of physics," and he worked out a wave equation to calculate the energy state of the hydrogen atom.

For Schrodinger, this heralded a more intuitive understanding of quantum states as "vibrational processes in atoms."

In simple terms, he saw electrons not as particles moving in orbit, but as waves with a continuous distribution of charge in three dimensions.

Heisenberg was dismissive of the emergence of wave mechanics.

At an academic conference in Munich, Schrodinger presented wave mechanics and related theories. After the meeting, Heisenberg complained to Pauli that wave theory could not explain a large number of quantum phenomena, including the photoelectric effect - the emission of electrons when a metal surface is illuminated - and the Stern-Gerlach effect, in which a beam of atoms is deflected in one of two ways as it passes through a spatially varying magnetic field.

In addition, describing a multiparticle system requires a wave function in an abstract hyperspace.

Overall, the wave function was undoubtedly a useful computational tool in Heisenberg's eyes, but it didn't seem to describe anything like real waves.

This is what he wrote:

Even if a consistent wave theory of matter could be developed in the usual three-dimensional space, it would be difficult to describe atomic processes in detail with the familiar pair of space-time concepts.

Nor did Schrodinger "sit still."

Over the next year, Schrodinger tried in vain to find a satisfactory physical explanation for wave mechanics.

At the Fifth Solvay Conference in Brussels in October 1927, Schrodinger again expressed the hope that "everything will indeed once again become intelligible in three dimensions" - a hope shared by few physicists at that time.

Since then, Schrodinger's wave mechanics has quickly become the mathematical form of choice for solving problems, but his theory of explaining individual processes in atoms in the spatial-time concept has few adherents.

Schrodinger was frustrated by this, because he felt that a time had come when physicists were no longer trying to visualize what was going on inside atoms.

The good news is that the debate over the two forms of quantum mechanics has not hindered the development of quantum mechanics itself.

In the spring of 1926, the equivalence of matrix mechanics and wave mechanics was established, which led to a series of subsequent developments

In June of that year, Born submitted his first paper on the phenomenon of collisions, in which he reinterpreted the Schrodinger theory in which the square of the amplitude of the wave function is the probability that a particle scatters in a particular direction after a collision.

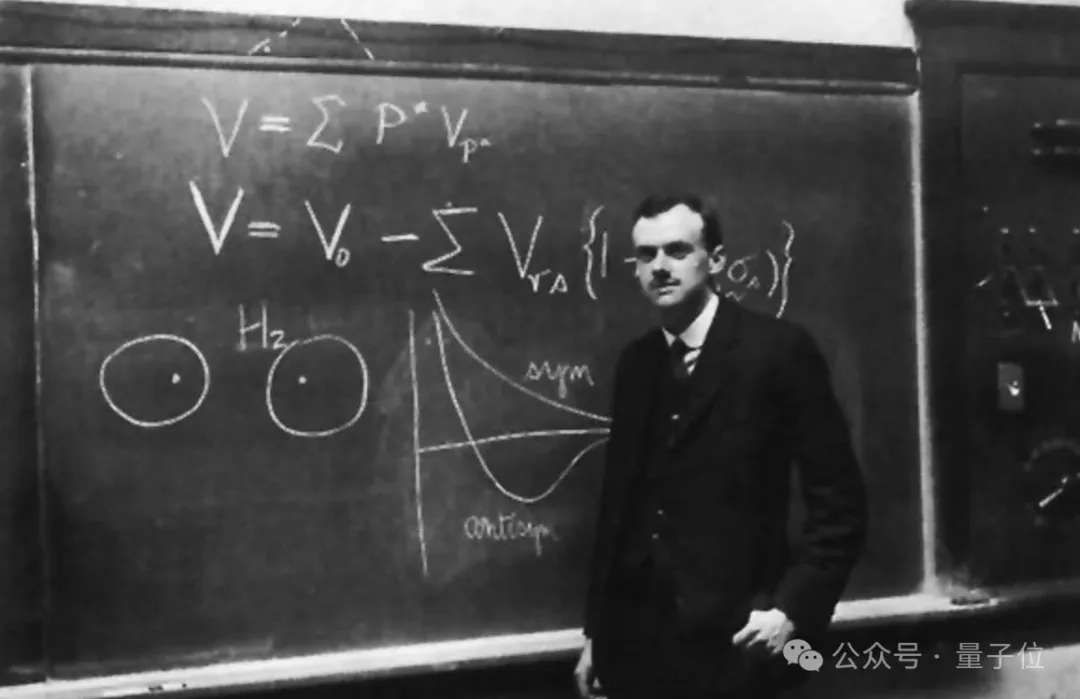

This was soon followed by the publication of a paper on transformation theory by British theoretical physicist Paul Dirac.

Transformation theory is a procedure and "picture" used by Dirac when he proposed quantum theory that describes quantum states in terms of probability amplitudes (rather than just the transitions between them).

Dirac was teaching quantum mechanics

According to rough incomplete statistics, in the two years between 1925 (when Heisenberg published his first paper on quantum mechanics) and 1927 (when Heisenberg published another seminal paper), scientists published nearly 200 articles on quantum mechanics.

In this development, Heisenberg introduced the concept of "uncertainty relations".

The concept proposes that the more precise an electron's position is, the less precise its momentum is (and vice versa).

Today, the uncertainty relation has become a central concept of quantum mechanics, which defines the degree of approximation when the classical mechanical description is used as an approximation.

Beginning in mid-1926, a growing number of physicists began to apply quantum theory to a wider range of practical problems, with promising results and even a deeper understanding of many areas than previously possible.

For example:

In a series of papers from 1926 to 1927, the modern American physicist Eugene Wigner showed "how empirical rules concerning atomic structure and molecular spectra can be derived by applying the symmetry principles of quantum mechanics and the mathematical techniques of group theory."

But!

The flood of papers on quantum mechanics has caught many physicists off guard - the pain of reading them is well known.

At that rate of development, it's really hard to keep up with the latest advances in the latest theories, and thinking about the deeper implications of new physics is a luxury use of brain cells.

For example, as soon as someone has mastered a new quantum mechanical technique or formula, another one comes along.

Or let's say a couple of physicists get together and when the paper is finished, it turns out that someone else/team has already done the same research and published it first.

This rapid pace of development led many physicists at the time to complain of "indigestion".

By the time of the Solvay Conference in 1927, most physicists believed that quantum mechanics had reached a provisional conclusion.

In their report, Heisenberg and Born declared quantum mechanics to be a "complete theory whose fundamental physical and mathematical assumptions can no longer be easily modified."

But some remain unconvinced.

In his opening speech on the last day of the conference, Hendrik Anton Lorenz, who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1902 at the age of 74 (known as "the Great old man of physics"), came forward to express his desire to also restore the description of the motion of electrons in space-time.

Schrodinger, Einstein, and French theoretical physicist Louis Victor de Broglie also expressed similar views that "there are serious problems with quantum mechanics."

Einstein wrote to Sommerfeld in November 1927:

"Quantum mechanics" may be a correct theory of statistical laws, but in general it is an inadequate understanding of individual fundamental processes.

Einstein stuck to his ideas for the rest of his life and never wavered.

But as time went on, the tide of public opinion began to turn, and the initial critics quickly became outsiders and even sided with the other side, calling the protests of Einstein, Schrodinger and others against quantum mechanics "nostalgia for the lost paradise of classical physics."

The general consensus is that, mathematically at least, quantum mechanics is as complete as it can be.

What remains is to continue along the path of modern physics.

As a result, most physicists are increasingly applying theory to practice.

"Within a few years," recalled Victor Weisskopf, a Jewish-American physicist who was Heisenberg's postdoctoral fellow and also Schrodinger's assistant, "questions that had been considered unsolvable for decades - such as the nature of molecular bonds, the structure of metals, and the radiation of atoms - were explained."

The above is the story of the birth and gradual affirmation of quantum mechanics a hundred years ago.

Until today, the deeper thinking and problems about the interpretation of quantum theoretical physics have been developed to the point that they tend to trigger discussions and discussions at the level of philosophical thinking.

Refer to the link: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-04217-0.

2025-02-17

2025-02-14

2025-02-13

13004184443

Room 607, 6th Floor, Building 9, Hongjing Xinhuiyuan, Qingpu District, Shanghai

gcfai@dongfangyuzhe.com

WeChat official account

friend link

13004184443

立即获取方案或咨询

top