Home > Information > News

#News ·2025-01-02

Who would have thought that in a paper in the medical field, Microsoft actually "exposed" the parameters of the OpenAI model!

Researcher: All parameters are estimates

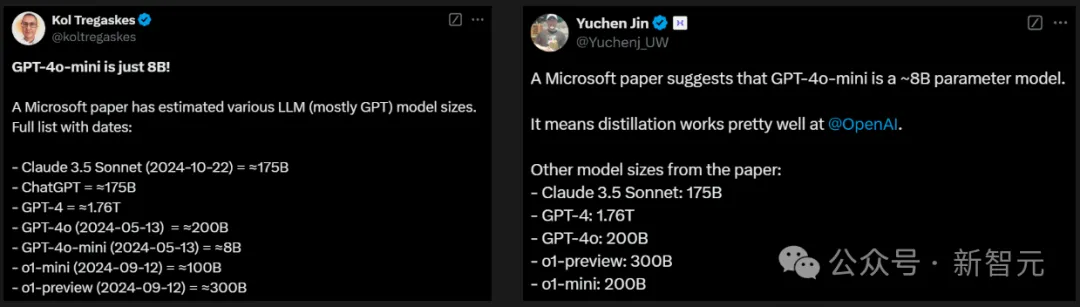

To everyone's disbelief, the GPT-4o series has so few parameters, and the mini version even has only 8B.

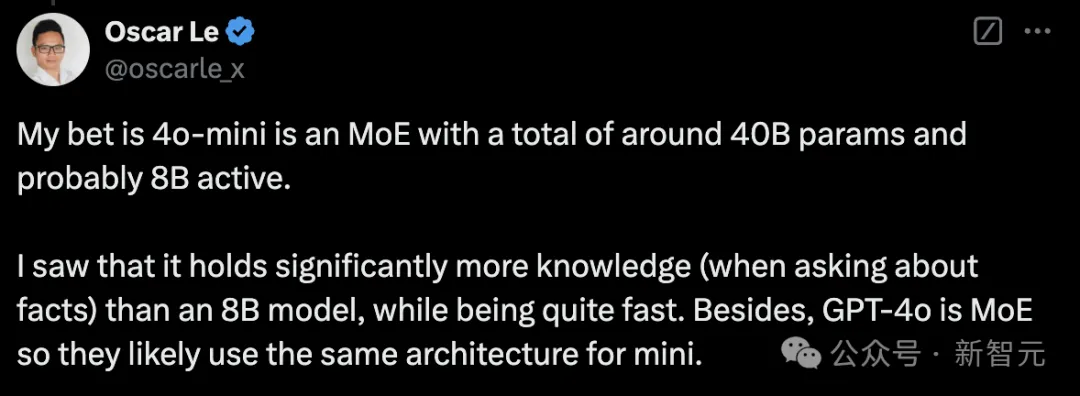

Some netizens speculated that the 4o mini is a MoE model with about 40B parameters, where the activation parameter is 8B.

Because he found that the 4o mini learned significantly more than the 8B model and ran faster at the same time.

Also, since GPT-4o is a MoE architecture, OpenAI may be using the same architecture on the mini version.

Another netizen expressed surprise that Claude 3.5 Sonnet parameters are equivalent to GPT-3 davinci.

The paper, from a team at Microsoft and the University of Washington, publishes a landmark assessment benchmark, MEDEC1, designed for medical error detection and correction in clinical notes.

Address: https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.19260

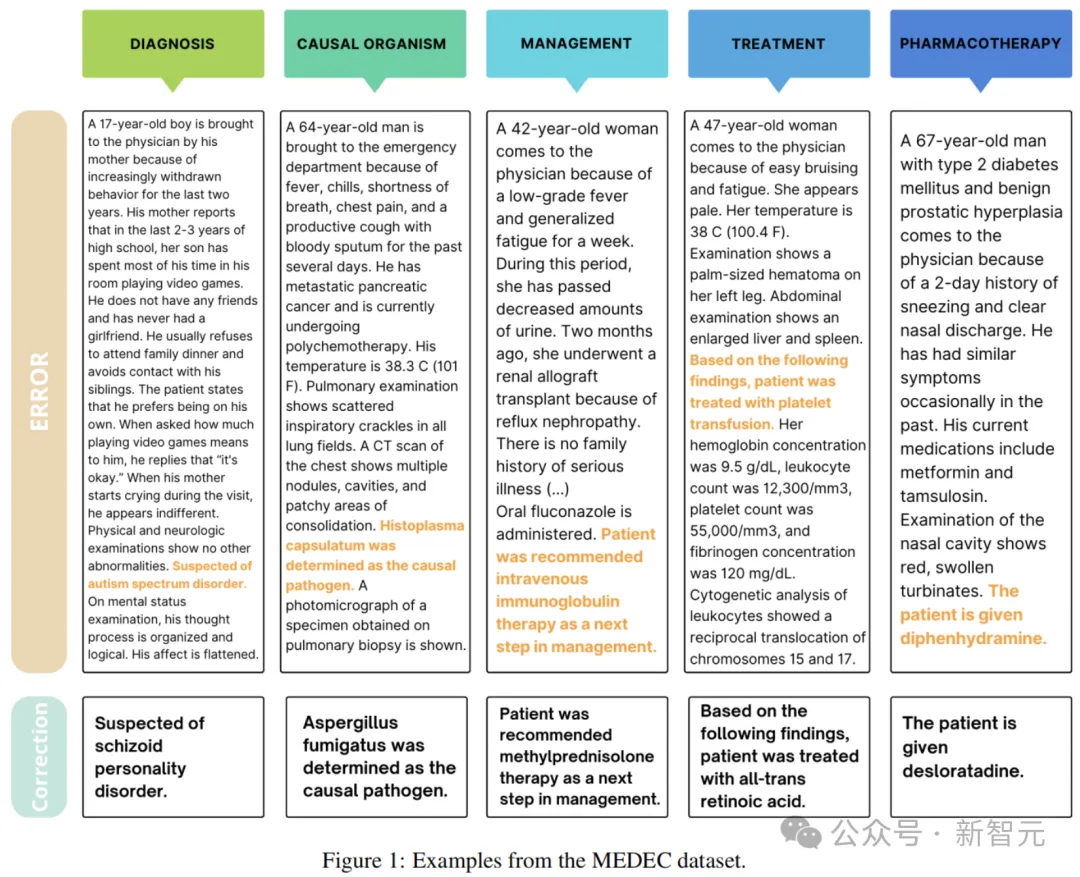

The benchmark covers five types of errors, including diagnosis, management, treatment, medication and causative agents.

MEDEC's data source collected 488 clinical notes from three U.S. hospital systems, for a total of 3,848 clinical texts.

It is worth mentioning that this data has not been previously accessed by any LLM, which can ensure the reliability of the assessment. The data set has been used in the MEDIQA-CORR shared task to evaluate the performance of 17 participating systems.

After obtaining the dataset MEDEC, the research team thoroughly tested current state-of-the-art models, including o1-preview, GPT-4, Claude 3.5 Sonnet, Gemini 2.0 Flash, and others, in medical error detection and correction tasks.

At the same time, they also invited two professional doctors to perform the same error detection task, and eventually pitted the AI against the human doctor results.

The results found that the latest LLM performed well in medical error detection and correction, but there was still a significant gap between AI and human doctors.

This also confirms from the side that MEDEC is a sufficiently challenging evaluation benchmark.

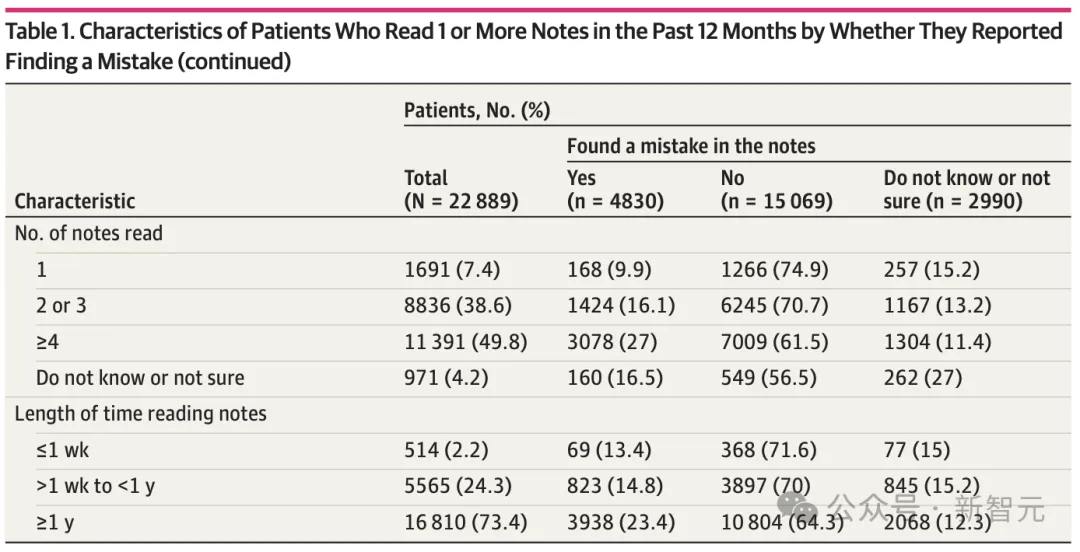

A study from a U.S. medical institute found that one out of every five patients who read clinical notes reported finding errors.

Forty percent of patients considered these errors to be serious, with the most common category of errors related to a current or past diagnosis.

At the same time, more and more medical documentation tasks (e.g., clinical note generation) are now performed by LLMS.

However, one of the main challenges of using LLM for medical documentation tasks is that it is prone to "hallucinations" that output some fictional content or misinformation that directly affects clinical decision making.

After all, there is no small thing in medicine, and the difference between one word and another can be the difference between life and death.

To mitigate these risks and ensure the safety of LLMS in medical content generation, a rigorous validation approach is critical. This validation requires benchmarks to assess whether the validation model can be fully automated.

A key task in the validation process is to detect and correct medical errors in clinical texts.

Thinking from the perspective of a human physician, identifying and correcting these errors requires not only medical expertise and field background, but sometimes extensive experience.

Until now, most research on (common-sense) error detection has focused on the general domain.

To this end, the Microsoft University of Washington team introduced a new dataset, MEDEC, and experimented with different leading LLMS, such as Claude 3.5 Sonnet, o1-preview, and Gemini 2.0 Flash.

"To our knowledge, this is the first publicly available benchmark and study for automated error detection and correction in clinical notes," the authors said.

The MEDEC dataset contained a total of 3,848 new datasets of clinical texts from different medical specialties, and the tagging task was performed by eight medical taggers.

As mentioned earlier, the dataset covers five types of errors, specifically:

(Note: These error types were selected after analyzing the most common types of questions on the Medical Board exam.)

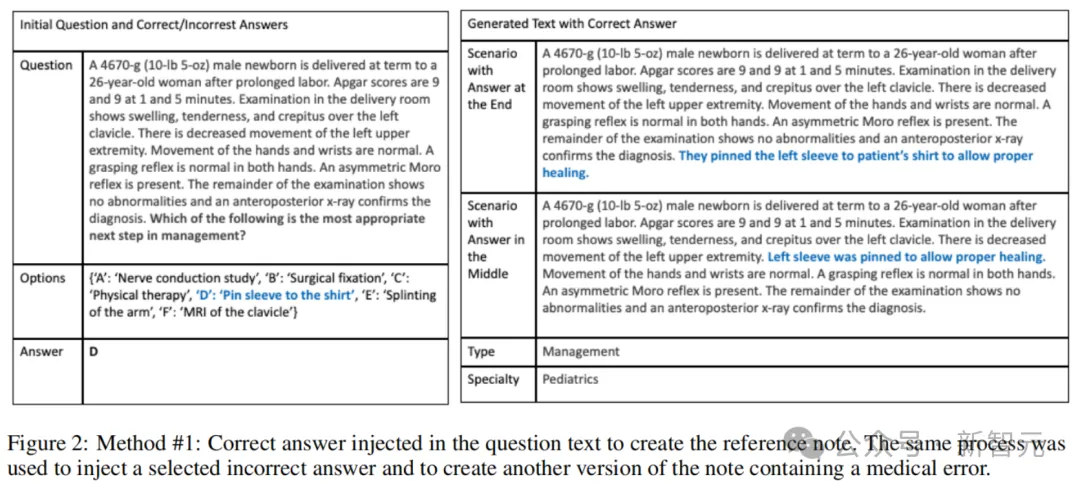

Figure 1 above shows an example from the MEDEC dataset. Each clinical text is either correct or contains an error created by one of two methods: Method #1 (MS) and Method #2 (UW).

In this approach, the authors make use of medical board examination questions from the MedQA collection.

Four annotators with a medical background refer to medical narratives and multiple choice questions from these exams, check the original questions and answers, inject incorrect answers into the scene text, and exclude pairs that contain errors or ambiguous information.

Medical taggers follow the following guidelines:

Finally, the researchers built the final dataset from two different scenarios (errors injected into the middle or end of the text), randomly selecting one correct version and one incorrect version for each note.

here, The authors used a database of real clinical notes from three University of Washington (UW) hospital systems (Harborview Medical Center, UW Medical Center, and Seattle Cancer Care Alliance) from 2009-2021.

The researchers randomly selected 488 of 17,453 diagnostic support records, which summarized the patient's condition and provided a basis for treatment.

A team of four medical students manually introduced errors into 244 of these records.

In the initial phase, each record is labeled with several candidate entities that are identified by QuickUMLS 4 as concepts for the Unified Medical Language System (UMLS).

The tagger can select a concise medical entity from these candidates, or create a new text segment (span). The segment was then marked with one of five error types.

The tagger then replaces the segment with a similar but different concept, and the error version is either designed by the tagger itself or generated through SNOMED - and LLM-based methods. This approach suggests alternative concepts to the tagger, but does not rely on input text. The medical annotator manually determines the concepts or errors that are eventually injected into the text.

In this process, each error fragment must contradict at least two other parts of the clinical note, and the tagger must provide a reasonable explanation for each introduced error.

The author used the Philter5 tool to automatically de-identify clinical notes after injection errors.

Each note was then independently reviewed by two taggers to ensure de-identifiers were accurate. Any disagreement is decided by the third tagger.

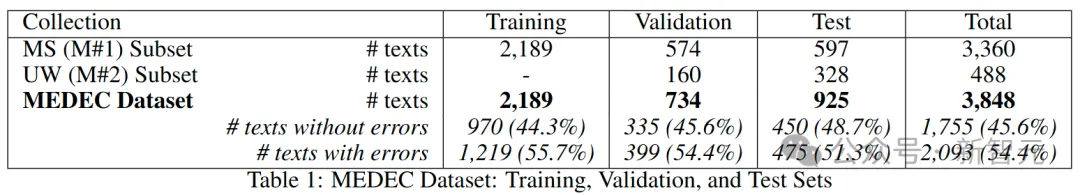

Table 1 below shows the division of the training set, verification set, and test set. Among them, the MS training set contained 2,189 clinical texts, the MS validation set contained 574 clinical texts, and the UW validation set contained 160 clinical texts.

The MEDEC test set consists of 597 clinical texts from the MS collection and 328 clinical texts from the UW dataset. In the test set, 51.3 percent of the notes contained errors, while 48.7 percent were correct.

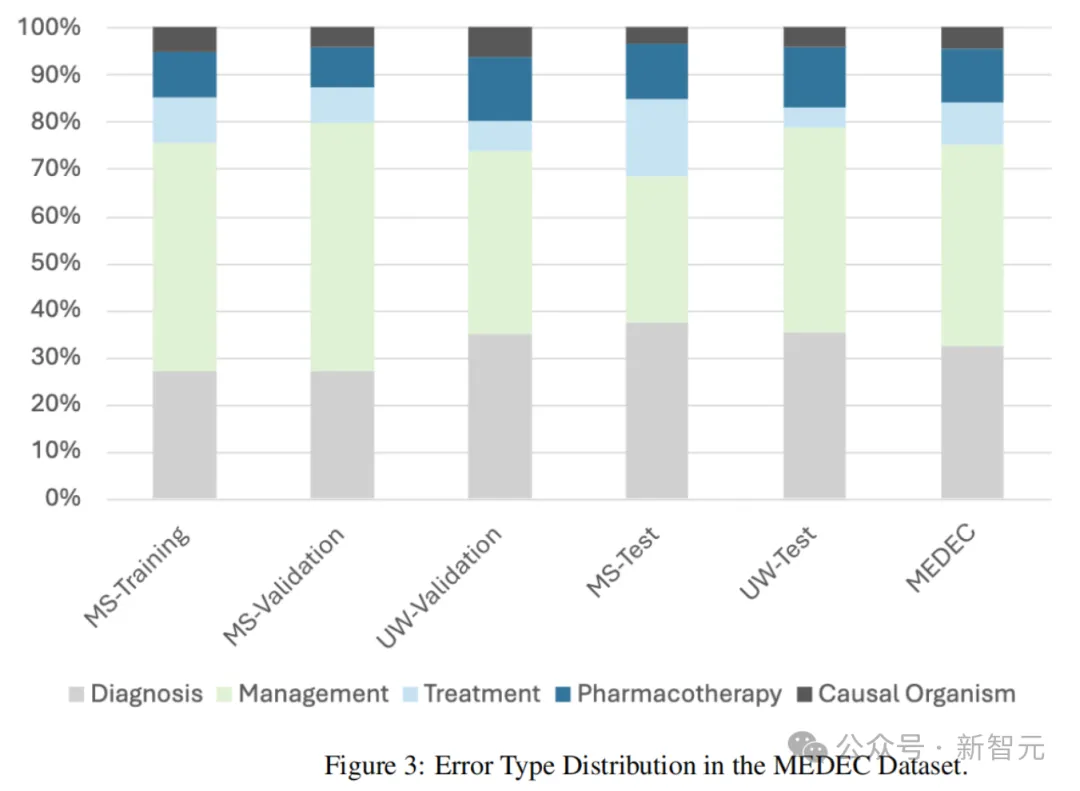

Figure 3 below shows the distribution of error types (diagnosis, management, treatment, medication, and causative agents) in the data set.

To evaluate the model's performance in the medical error detection and correction task, the authors divided the process into three subtasks:

For comparison, they built a solution based on LLM, using two different prompt words to generate the output needed to evaluate the model's performance in these three subtasks:

The following is a medical account of one patient. You are a skilled physician reviewing these clinical texts. The text is either correct or contains an error. Each line in the text is a sentence. Each line begins with the sentence ID, followed by a vertical bar symbol, followed by the sentence you want to check. Check every sentence in the text. If the text is CORRECT, the following output is returned: CORRECT. If there is a medical error in the text related to treatment, management, etiology, or diagnosis, the sentence ID containing the error is returned, followed by a space, followed by the corrected sentence. Finding and correcting errors requires medical knowledge and reasoning.

Here is an example.

A 35-year-old woman complained to her doctor of hand pain and stiffness. 1 She said the pain started six weeks ago, a few days after she overcame a mild upper respiratory infection. (...) 9 Bilateral X-rays of both hands showed a slight periarticular osteopenia around the fifth metacarpal knuckle of the left hand. 10 Give methotrexate.

In this example, the error occurs in the sentence number 10: "Give methotrexate". Amended to read: "Administer prednisone". The output is: 10 1 Prednisone is given. End of example.

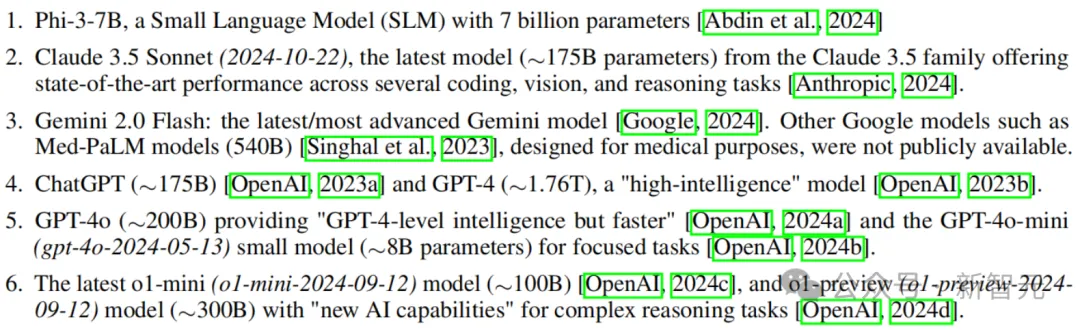

The researchers experimented with several recent language models:

It is worth noting that the number of parameters in most models is estimated and is used primarily to help understand model performance. A few models, such as Phi-3 and Claude, require a small amount of automatic post-processing to fix formatting problems.

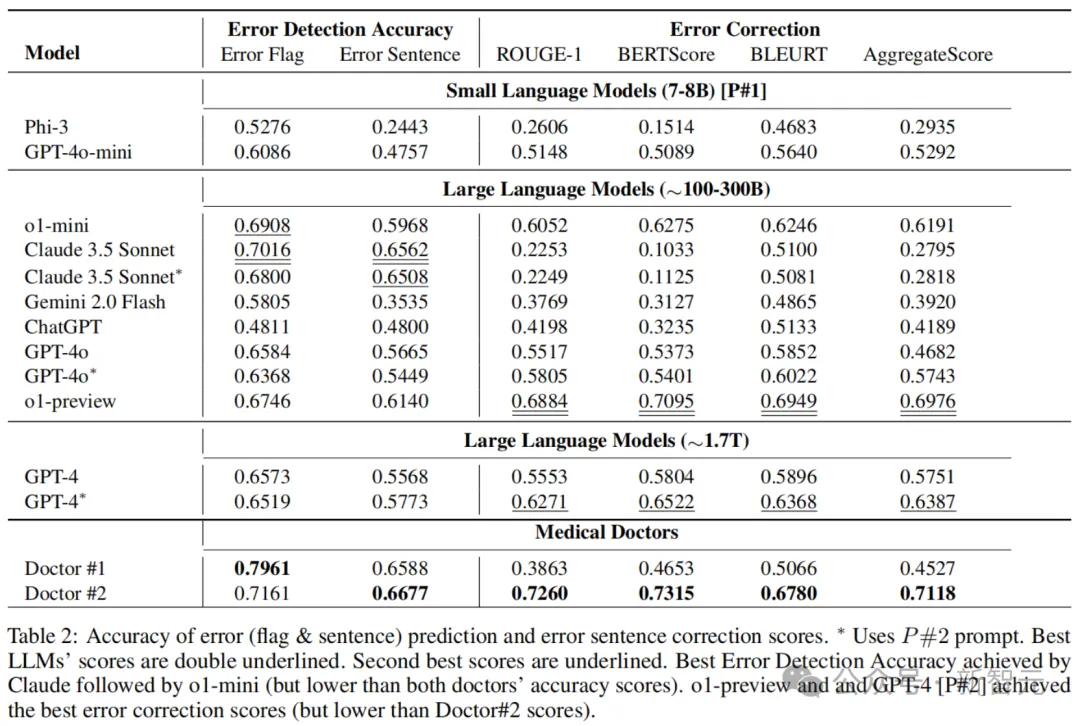

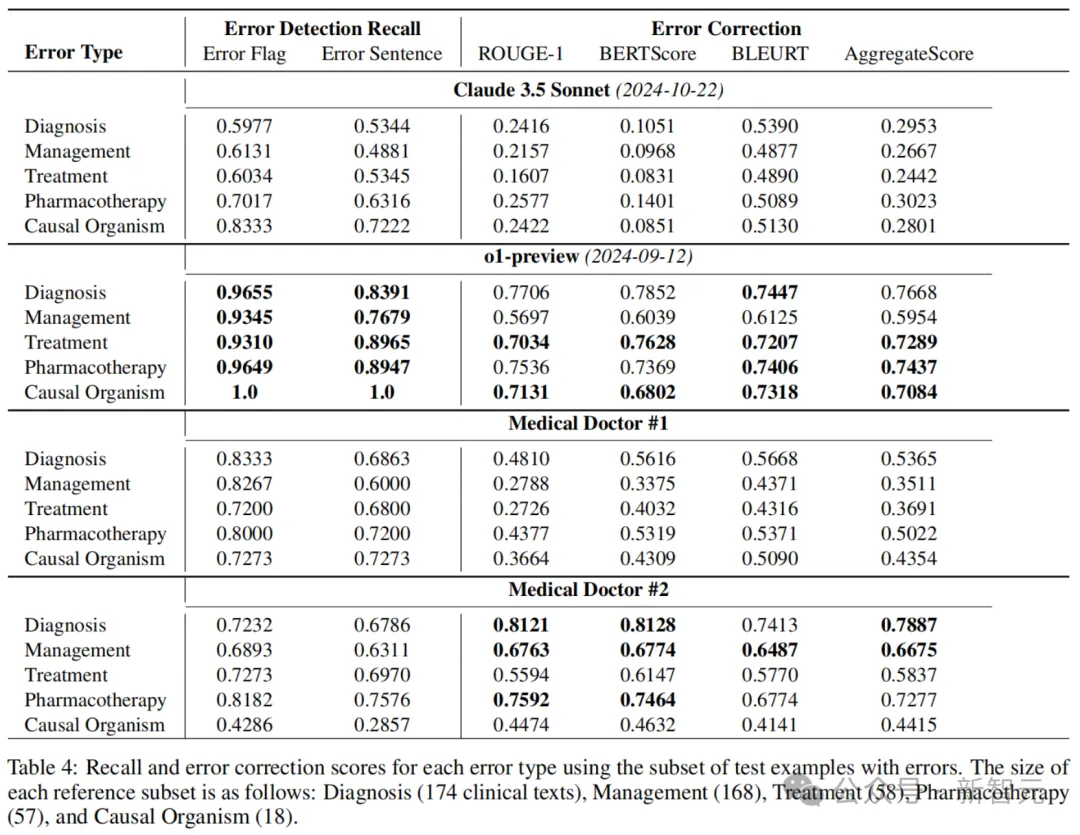

Table 2 below shows the results manually annotated by medical practitioners and the results of multiple recent LLMS using the above two prompt words.

In terms of error flag detection, Claude 3.5 Sonnet was superior to other methods with an accuracy of 70.16% and 65.62% in error sentence detection.

The o1-mini achieved the second highest accuracy of 69.08% in error flag detection.

In terms of error correction, o1-preview achieved the best performance with an Aggregate Score of 0.698, well ahead of the second place GPT-4 [P#2] with 0.639.

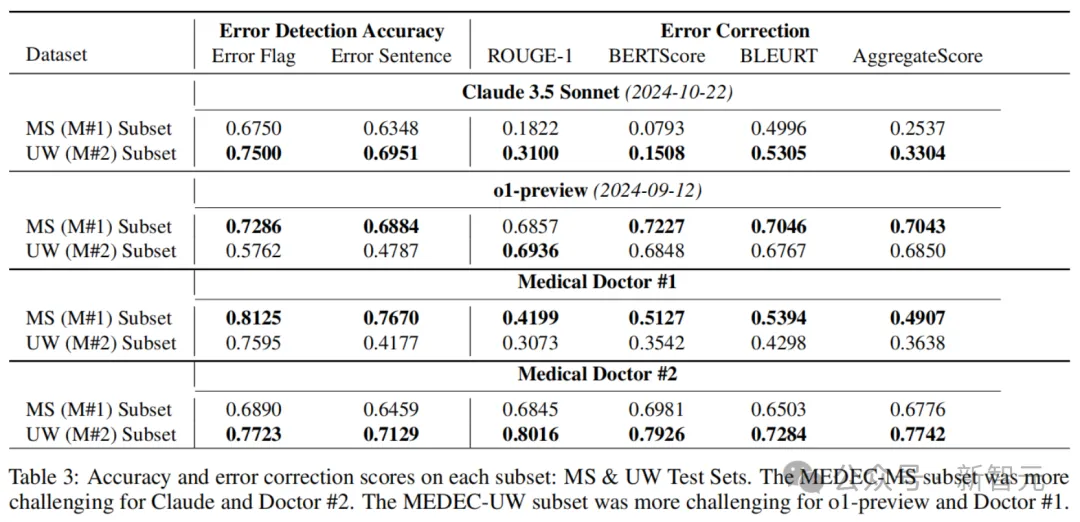

Table 3 below shows the error detection accuracy and error correction scores for each dataset (MEDEC-MS and MEDEC-UW). Among them, the MS subset is more challenging for Claude 3.5 Sonnet and Doctor #2, while the UW subset is more challenging for o1-preview and Doctor #1.

The results showed that the latest LLMS performed well in error detection and correction compared to doctors' scores, but still lagged behind human doctors in these tasks.

This may be because such error detection and correction tasks are relatively rare on the web and in medical textbooks, i.e. LLMS are less likely to encounter relevant data during pre-training.

This can be seen in the results of o1-preview, which achieved 73% and 69% accuracy in error and sentence detection, respectively, on MS subsets built on public clinical text, but only 58% and 48% accuracy on private UW sets.

Another factor is that the task requires analyzing and correcting existing non-LLM-generated text, which can be more difficult than drafting a new answer from zero.

Table 4 below shows error detection recall rates and error correction scores for each error type (diagnostic, administrative, therapeutic, medicated, and causative microbiome).

It can be seen that o1-preview has a significantly higher recall rate than Claude 3.5 Sonnet and both doctors in error flags and sentence detection. But when the accuracy results were combined (see Table 2), doctors performed better on accuracy.

These results show that the models have significant problems with accuracy, and that the AI overpredicts the presence of errors (i.e., hallucinations) in many cases, compared to doctors.

In addition, the results show that there is a ranking difference between classification performance and error correction generation performance.

For example, Claude 3.5 Sonnet ranks first among all models in the accuracy of error flags and sentence detection, but last in the corrected generation score (see Table 2).

In addition, o1-preview ranks fourth in error detection accuracy among all LLMS, but first and far ahead in corrective generation. The same pattern can be observed between two medical doctors.

The above phenomenon, which can be explained by the difficulty of correcting the generation task, may also reflect the limitations of the current SOTA text generation evaluation metrics in capturing synonyms and similarities in medical texts.

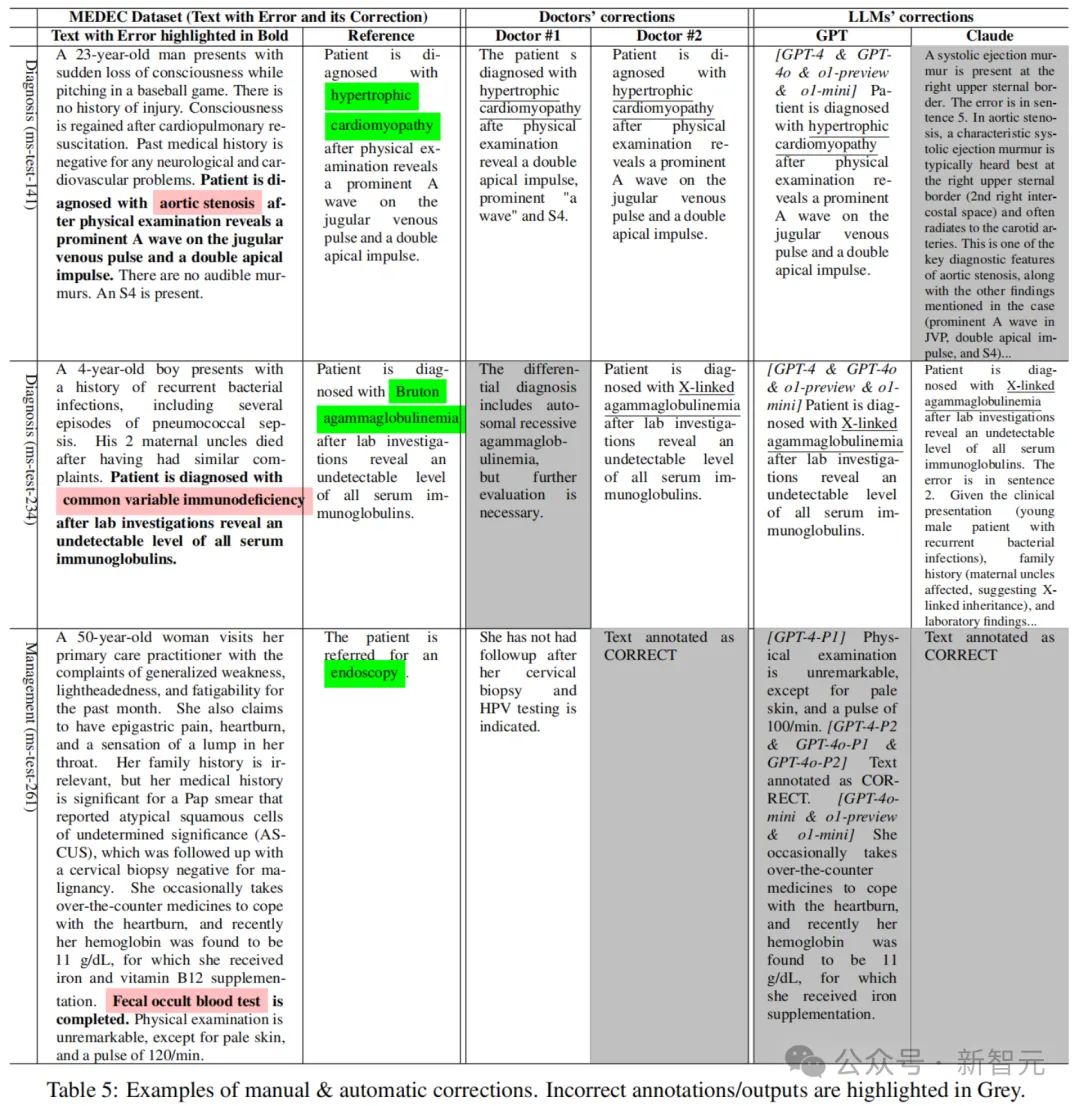

Table 5 shows reference text, physician annotations, and corrective examples automatically generated by the Claude 3.5 Sonnet and GPT models.

For example, the reference correction for the second example indicated that the patient was diagnosed with Bruton agammaglobulinemia, while the correct answer provided by the LLM mentioned X-linked agammaglobulinemia (a synonym for this rare genetic disorder).

Also, some LLMS (like Claude) provide longer answers/corrections with more explanations attached. A similar phenomenon was seen in the doctor's annotations, where doctor #1 provided a longer correction than doctor #2, and the two doctors disagreed in some examples/cases, reflecting the differences in style and content of clinical notes written by different doctors/specialists.

The next step in the research on medical error detection and correction is to introduce more examples in prompt words and perform example optimization.

Wen-wai Yim

Wen-wai Yim is a senior application scientist at Microsoft.

She earned a bachelor's degree in bioengineering from UCSD and a doctorate in Biomedical and Health Information from the University of Washington, where her research interests included extracting clinical events from clinical and radiological notes and making cancer stage predictions.

In addition, he worked as a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University, developing methods for extracting information from free-form clinical notes and combining this information with metadata from electronic medical records.

Her research interests include clinical natural language understanding from clinical notes and medical conversations, and generating clinical note language from structured and unstructured data.

Yujuan Fu

Yujuan Fu is a doctoral student in medical informatics at the University of Washington.

Previously, she received a Bachelor's degree in electrical and Computer Engineering from Shanghai Jiao Tong University and a Bachelor's degree in Data science from the University of Michigan.

The research area is natural language processing for health: fine-tuning large language models through instructions, including information extraction, summarization, common-sense reasoning, machine translation, and fact consistency assessment.

Zhaoyi Sun

Zhaoyi Sun is a doctoral student in Biomedical and Health Informatics at the University of Washington and is part of the UW-BioNLP team, supervised by Dr. Meliha Yetisgen.

Prior to that, he received a bachelor's degree in Chemistry from Nanjing University and a master's degree in Health Informatics from Cornell University.

His research focuses on the application of LLM to error detection in medical question answering and clinical notes, and is interested in multimodal deep learning research combining biomedical images and text, with the goal of improving the efficiency and effectiveness of natural language processing technology in clinical applications.

Fei Xia

Fei Xia is a professor in the Department of Linguistics at the University of Washington and co-organizer of the UW/Microsoft Workshop. Prior to that, he was a researcher at IBM T. J. Watson Research Center.

She received her bachelor's degree in Computer Science from Peking University and her master's and doctoral degrees in Computing and Information Science from the University of Pennsylvania.

While at Penn, she was a team leader on the Chinese Treebank project and a team member on the XTAG project. Doctoral thesis supervisors were Dr. Martha Palmer and Dr. Aravind Joshi.

2025-02-17

2025-02-14

2025-02-13

13004184443

Room 607, 6th Floor, Building 9, Hongjing Xinhuiyuan, Qingpu District, Shanghai

gcfai@dongfangyuzhe.com

WeChat official account

friend link

13004184443

立即获取方案或咨询

top